Memory Lane

(With a little help from prompt to image technology)

As far back as I can remember my mother had just one rule, that rule was “Be home in time for supper” and that was it. My father gave me one piece of advice in my entire childhood and that was “You can never catch up on lost sleep.” Looking back that was pretty good information.

We lived in a rural farming area about sixty kilometers outside of London on a country lane in a little cottage. As early as the age of six they would just let me go out the door with absolutely no boundaries (except the be home for dinner part). I would wander alone across our front yard, pass under the huge elmwood tree, cross the dirt lane, push my way through the hedges and head out onto the ancient farm that called to me.

One morning as I walked under row after row of fresh tomato vines an overwhelming fragrance came over me. For a reason only understood by a six-year-old, I took off all my clothes, tucked them under my head and fell deeply asleep right there beneath a ceiling of ripe tomatoes. I woke to a farm worker shaking me and a crowd of pickers coming up the row behind her. She knew me and my mother, and kindly said something like “How many times do I …….” Given my attention span, that’s about all I heard.

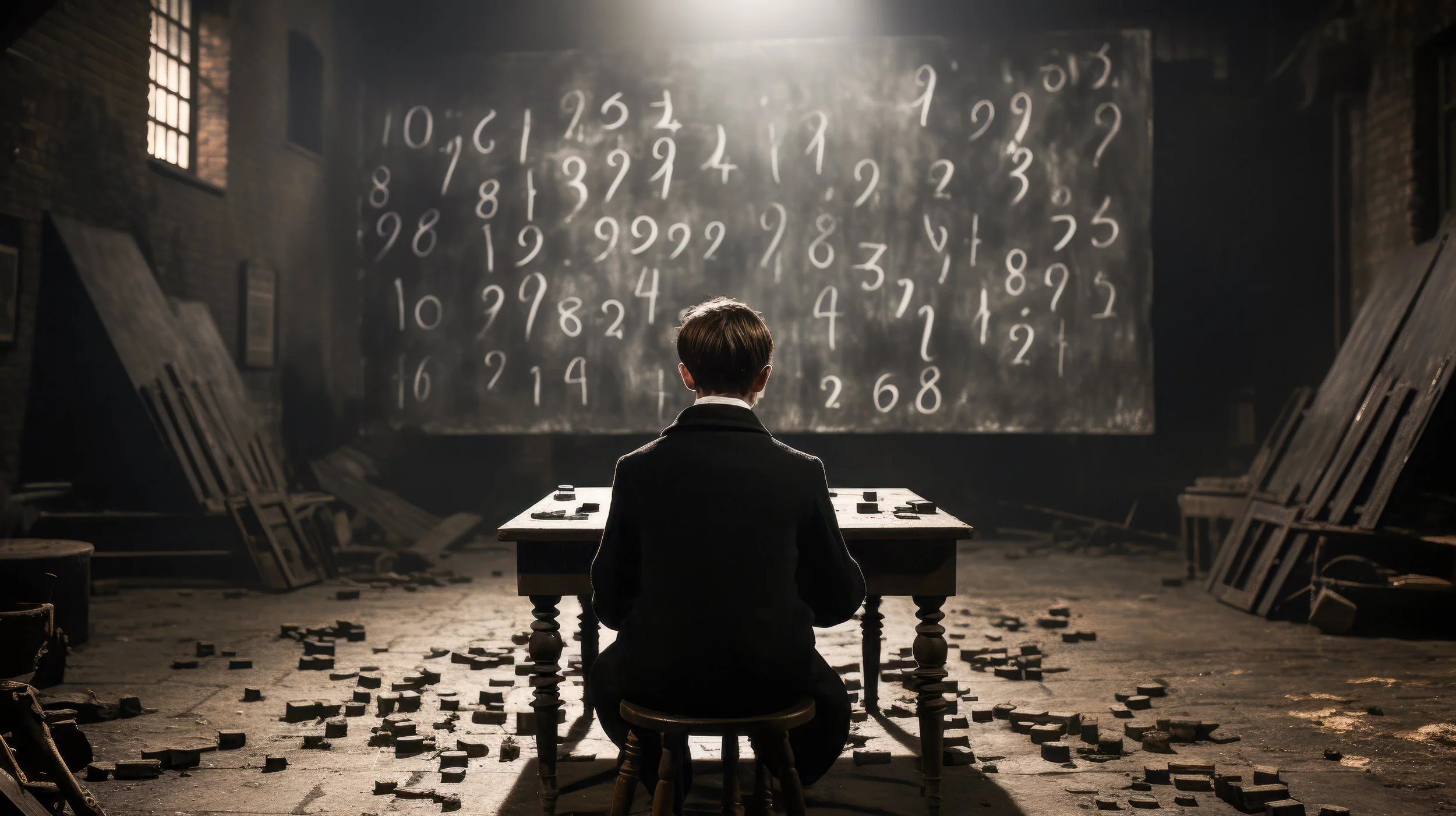

It was my first day at school and the small firecracker blew off less than a foot from my right ear. It happened in our school yard, and no one seemed to take notice except the older kid and his pals that threw it ar me. It was a different world growing up in the UK in the late 1940’s and I just didn’t fit in. At eight I didn’t even know how to tell time.

Have you ever wondered how tall the waves are in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean? To me they looked to be as tall as houses, but that huge Ocean Liner slid thru them as though it were calm. I was 8 years old, and my family came from the UK to the US on the Queen Mary. I am telling you that I was the most unconscious kid that ever walked the earth. Now that you know that you should not be surprised by anything else I might say from here on out. How’s this one for an example? I actually thought that the sidewalks in the US would be covered with gold. Yes, I said it and it feels so good to finally get it out.

So, my parents picked up my brother and me and moved us to the US and my father’s hometown of East Boston. I would say that that was, maybe, one of the best things that ever happened to me because as soon as we got here, I flourished.

We settled into a modest home on the third floor of a triple decker walk up on a dead-end street a few hundred yards from the docks at the Boston Harbor. I had a single pair of jeans. When my mother washed them, I would put them on damp and go out as if that were perfectly normal. That place was home, like the beginning and end of something extraordinary, a real life. I miss it with all my heart.

It was in that triple decker that I got my first encountered with the call of art. My grandfather was a working artist with a soul as true and steady as his brushstrokes, he gave me a precious gift, a license to make stuff and call it art. He taught me how to tell time within the first ten minutes of our meeting, he also taught me to see that light had characteristics way beyond volume. It had a language of its own, like when it danced as it reflected off water, and the endless emotional play of color. And that’s how my visual journey began, guided by the wisdom of an old man who still saw the world through a kaleidoscope of imagination. Sometimes, on a good day, I see myself as that old man refusing to stop living in awe of what I see.

If you are wondering why I am telling you this. There are two reasons. One, so you might get to know me a little and the other because that freedom my parents unknowingly gave me way back on the farm, stuck for my entire life. It did not come without pain or misery, but it is what led me to photography in the first place.

Looking back, I’m thinking that it had to be destiny that intervened by way of a scholarship to the MFA in Boston. I walked thru those Museum doors with absolutely no concept of what was about to hit me. It was the first time I had ever seen world class art like they had everywhere from the mind-blowing African Masks to the impossible paintings. I still remember the emotion of seeing the works from the great painters like, Van Gogh, Picasso, Renoir right there, two feet in front of me. I took it all in, hook, line, and sinker. I was humbled, shaken, picked up and dropped into the middle of a wild and compelling ride that would consume the rest of my life. The world of art and photography begrudgingly unraveled before my eyes, giving up its secrets only after the proper amount of blood had been shed. Those three years confirmed my growing belief about hard work and determination. I was now convinced that it was for sure a real thing, pretty much, equal to God given talent; that’s my story and I am sticking to it.

Then the military called by way of the draft, and I answered with a healthy bit of unease. I trained as a helicopter maintenance man and door gunner. There are a thousand stories here, but I will spare you except to say that those years spawned the idea behind my “Southern Nights” collection. Amidst the rigid discipline and adrenaline-fueled routines, my passion for the visual arts stood fast, a constant companion on my journey. That’s where I began my crazed compulsion to make photographs every day.

After serving my military time, I dedicated a yearlong immersion into all thing’s photography at the best kept secret in Boston … Franklin Institute. Those professional photographers and teachers hammered into me the fact that the bottom line of being a professional photographer would be to develop an iron clad, repeatable skill set. All the creative ideas in the world would be wasted if you couldn’t manifest them onto film. In those days the height of professional photography meant 4X5 transparency film. A combination of scientific sorcery and black magic. It meant moving a huge camera on a heavy tripod to the exact right spot, focusing under a black cloth, figuring the bellows extension formula, and incorporating that into a best guess as to the right exposure according to two different light meters, all as the light was changing. It’s no wonder that photographers from that era were held in such a mixed esteem, kind of somewhere between Albert Einstein and Bozo the Clown. That was the longest year of my life. I could not wait to get out. Although I was learning so much, I had a knawing feeling as if I were in prison. I was chafing at the bit to get out in the world and let myself loose.

In time my cameras become extensions of my very being, witnessing the flow of so many advertising campaigns that have carried me to the far corners of the world. I recall one shoot in particular, a single adventure that transported me from Nike in Oregon to Mellon Bank in Chicago, BMW in Germany, British Air in the UK, and even to The Bank of China in Beijing.

But just to let you know that it has not all been a bed of roses. There have been times when I have almost given up. The pain of constantly traveling away from my family, the heart break of divorce, the message from my sister left at my hotel that came as I was working in Amsterdam. It read “Georgie, its Mary, Mum died.”

Somewhere along the line there have been an endless series of twists and turns, at one point leading me to build and manage two remarkable award-winning creative service groups for national and multinational corporations. It was there that I photographed so much that I estimate I exposed millions of frames of film in every format available. I found time to study with some of the world’s greatest photographers such as Arnold Newman, Jay Maisel and Steve Grohe. I photographed Ann Wang and John Updike for their book covers. I have been grateful to receive recognition and awards for my photography, which have been an encouragement and validation of my journey. I am a lifetime member of the American Society of Media Photographers. The truth is that none of that really matters. What matters is that I am one of those guys and gals that when you look at our images on a website or a magazine or a poster or a billboard you see work that moves you. That’s the takeaway I leave with you.

All these years later I am positive beyond any doubt that my grandfather would be so proud to know that I am still “making stuff and calling it art.”